Medical Management

- Nursing Assessment

- Nursing Diagnosis

- Nursing Care Planning and Goals

- Nursing Interventions

- Evaluation

- Documentation Guidelines

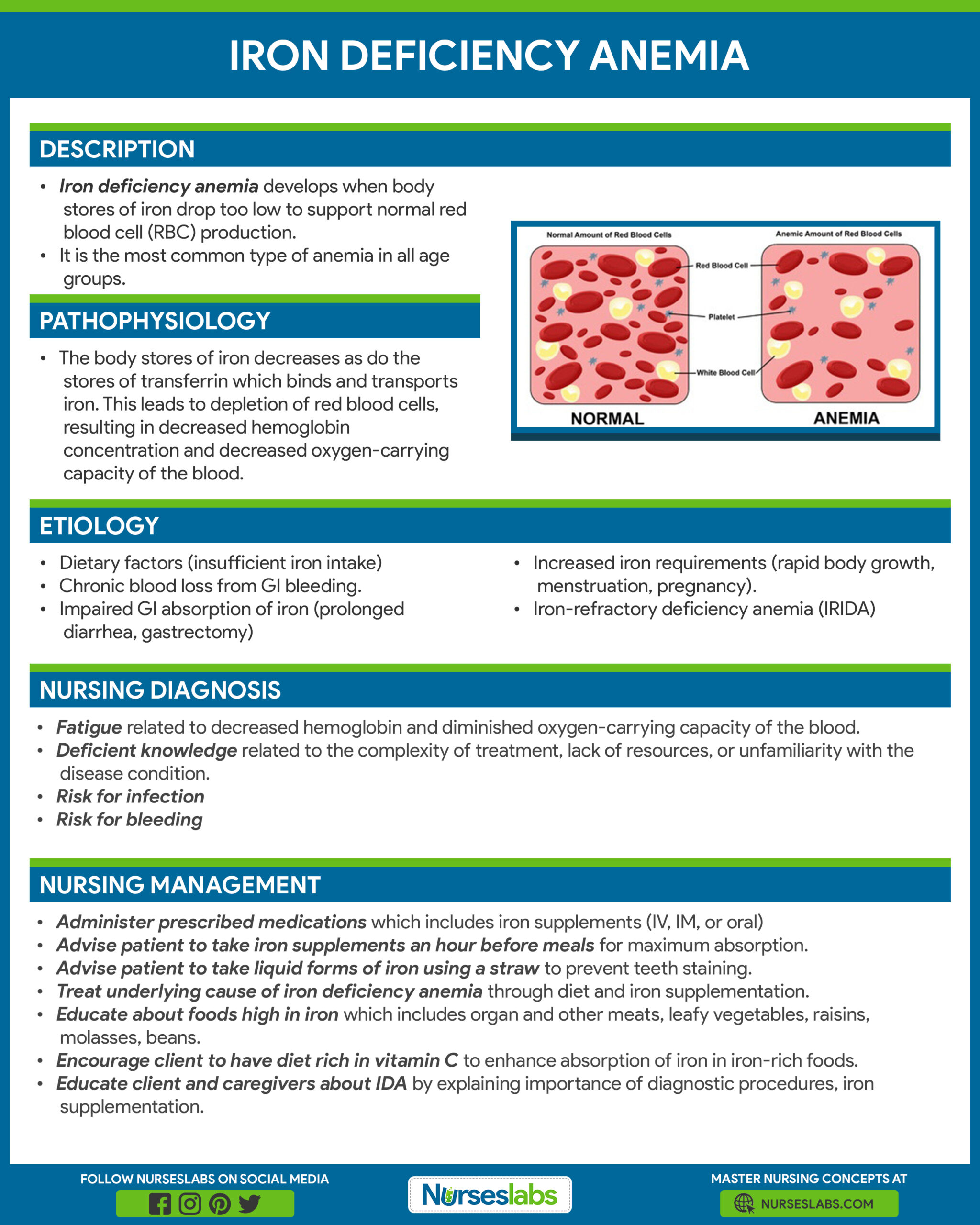

What is Iron Deficiency Anemia

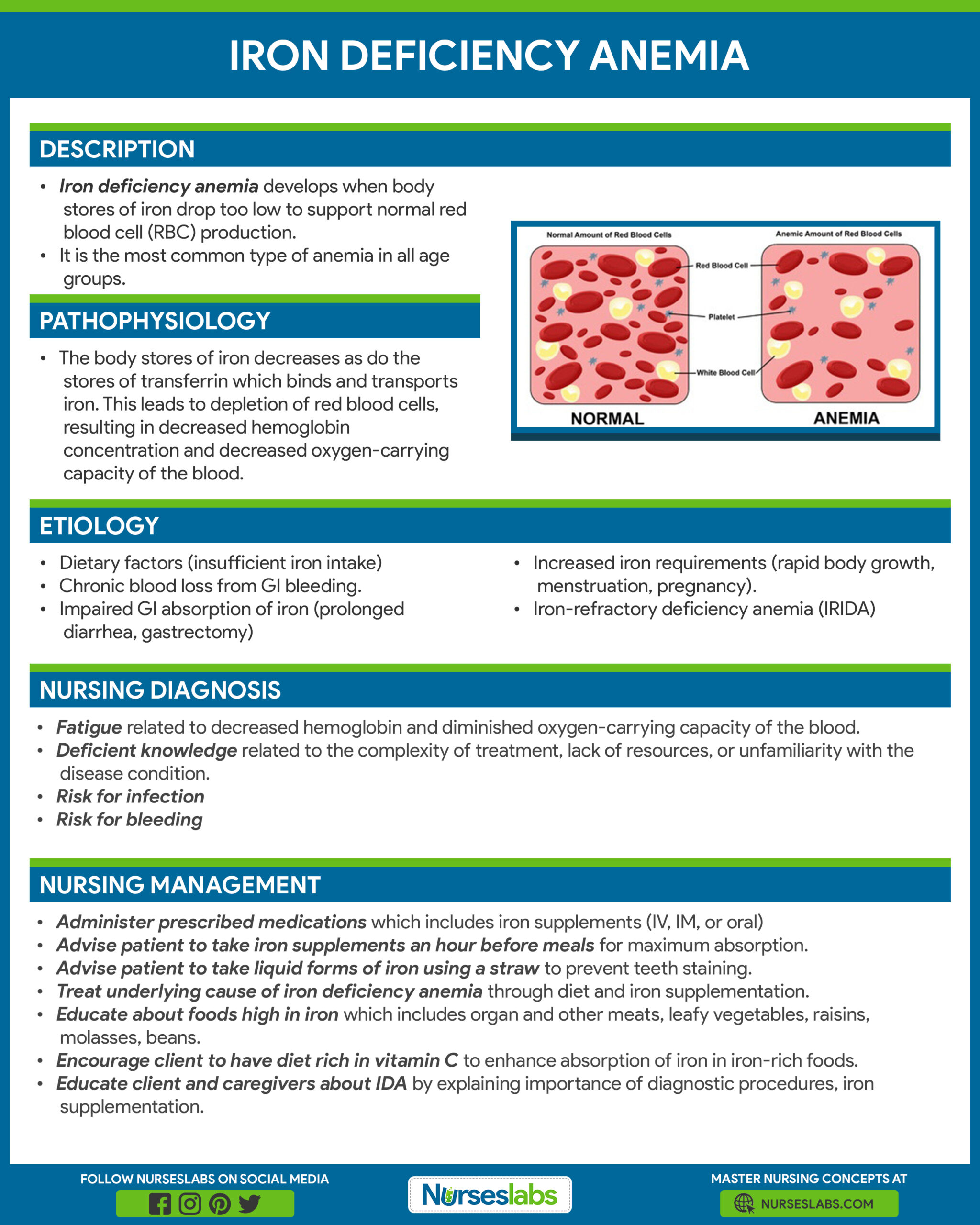

- Iron deficiency anemia develops when the body’s stores of iron drop too low to support normal red blood cell (RBC) production.

- Iron equilibrium in the body normally is regulated carefully to ensure that sufficient iron is absorbed in order to compensate for body losses of iron.

- Iron deficiency is defined as a decreased total iron body content.

- Iron deficiency anemia occurs when iron deficiency is severe enough to diminish erythropoiesis and cause the development of anemia.

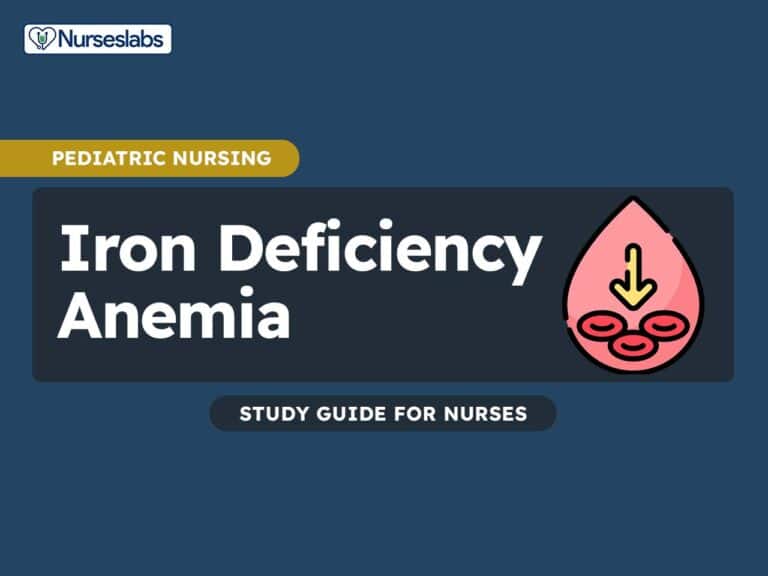

Pathophysiology

Iron is vital for all living organisms because it is essential for multiple metabolic processes, including oxygen transport, DNA synthesis, and electron transport.

- Iron equilibrium in the body is regulated carefully to ensure that sufficient iron is absorbed in order to compensate for body losses of iron.

- Whereas body loss of iron quantitatively is as important as absorption in terms of maintaining iron equilibrium, it is a more passive process than absorption.

- In healthy people, the body concentration of iron (approximately 60 parts per million [ppm]) is regulated carefully by absorptive cells in the proximal small intestine, which alter iron absorption to match body losses of iron.

- Persistent errors in iron balance lead to either iron deficiency anemia or hemosiderosis. Both are disorders with potentially adverse consequences.

- Iron uptake in the proximal small bowel occurs by 3 separate pathways; these are the heme pathway and 2 distinct pathways for ferric and ferrous iron.

- Heme iron is not chelated and precipitated by numerous dietary constituent that renders nonheme iron nonabsorbable, such as phytates, phosphates, tannates, oxalates, and carbonates.

Statistics and Incidences

Iron deficiency is the most prevalent single deficiency state on a worldwide basis.

- In North America and Europe, iron deficiency is most common in women of childbearing age and is a manifestation of hemorrhage.

- Depending upon the criteria used for the diagnosis of iron deficiency, approximately 4-8% of premenopausal women are iron deficient.

- A study of the national primary care database for Italy, Belgium, Germany, and Spain determined that annual incidence rates of iron deficiency anemia ranged from 7.2 to 13.96 per 1,000 person-years.

- Higher rates were found in females, younger and older persons, patients with gastrointestinal diseases, pregnant women and women with a history of menometrorrhagia, and users of aspirin and/or antacids.

- Infants consuming cow milk have a greater incidence of iron deficiency because bovine milk has a higher concentration of calcium, which competes with iron for absorption.

- During childbearing years, an adult female loses an average of 2 mg of iron daily and must absorb a similar quantity of iron in order to maintain equilibrium; because the average woman eats less than the average man does, she must be more than twice as efficient in absorbing dietary iron in order to maintain equilibrium and avoid developing iron deficiency anemia.

Causes

Causes of iron deficiency anemia may include:

- Dietary factors. Meat provides a source of heme iron, which is less affected by the dietary constituents that markedly diminish bioavailability than nonheme iron is; the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia is low in geographic areas where meat is an important constituent of the diet; in areas where meat is sparse, iron deficiency is commonplace.

- Hemorrhage.Bleeding for any reason produces iron depletion; if sufficient blood loss occurs, iron deficiency anemia ensues.

- Hemosiderinuria, hemoglobinuria, and pulmonary hemosiderosis. Iron deficiency anemia can occur from loss of body iron in the urine; if a freshly obtained urine specimen appears bloody but contains no red blood cells, suspect hemoglobinuria.

- Malabsorption of iron. Prolonged achlorhydria may produce iron deficiency because acidic conditions are required to release ferric iron from food; then, it can be chelated with mucins and other substances (e.g., amino acids, sugars, amino acids, or amides) to keep it soluble and available for absorption in the more alkaline duodenum.

- Iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA). Iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) is a hereditary disorder marked by with iron deficiency anemia that is typically unresponsive to oral iron supplementation and may be only partially responsive to parenteral iron therapy.

Clinical Manifestations

The signs of iron deficiency anemia include:

- Below average body weight. The child with iron deficiency anemia consumes more calcium than other nutrients, making them lighter than the average weight for their age.

- Pale skin and mucous membranes. The hemoglobin in red blood cells gives blood its red color, so low levels during iron deficiency make the blood less red; that’s why the skin and mucous membranes can lose its healthy, rosy color in people with iron deficiency.

- Anorexia. Loss of appetite is common, with milk as their only food source.

- Growth retardation. Due to a decrease in the consumption of other food sources, the growth of the child becomes stunted.

- Listlessness. The child who has less hemoglobin in the blood becomes listless and weak due to a decrease in oxygen circulating toward the brain.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

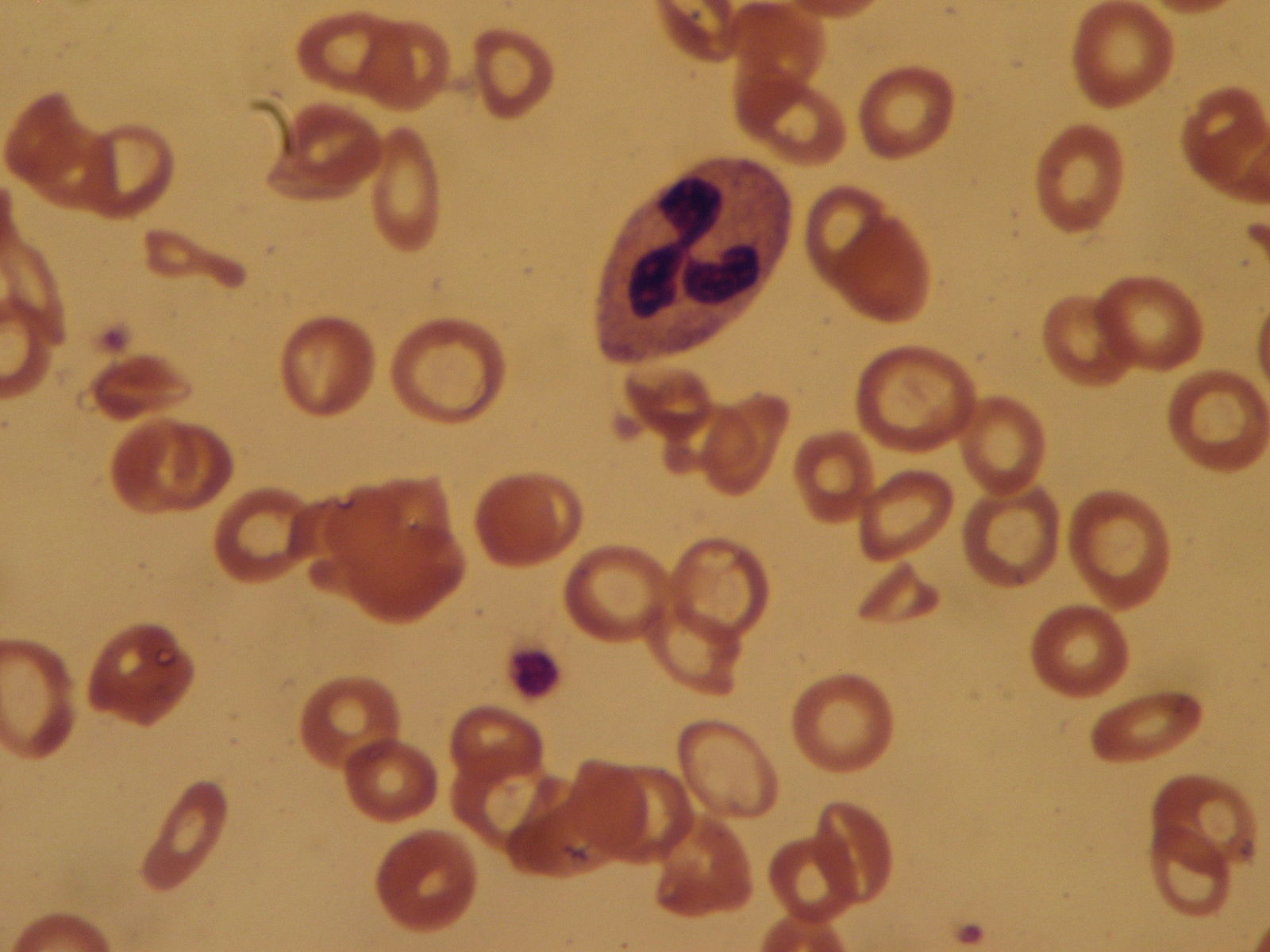

Although the history and physical examination can lead to the recognition of the condition and help establish the etiology, iron deficiency anemia is primarily a laboratory diagnosis.

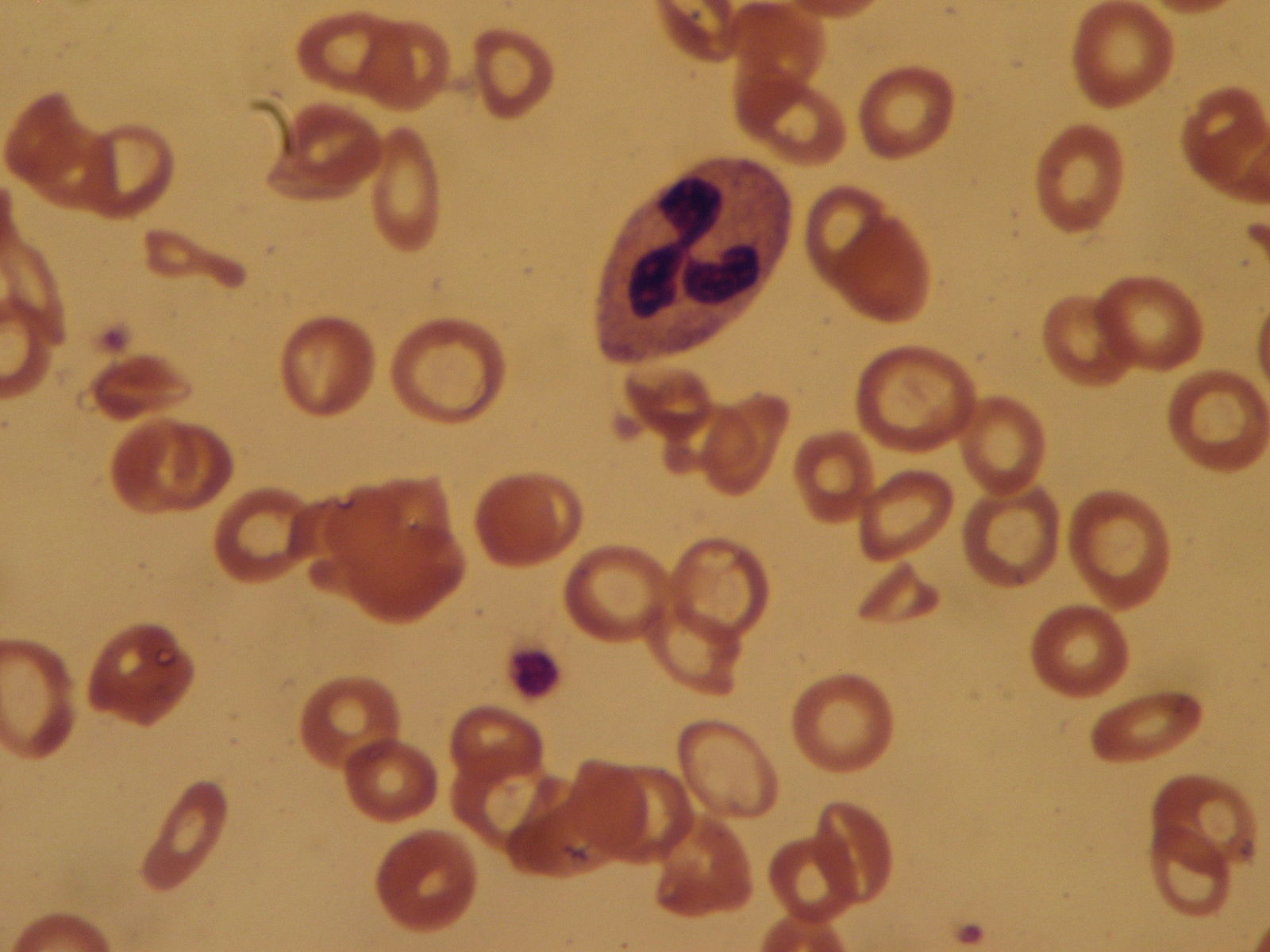

- Complete blood count. The CBC documents the severity of the anemia. In chronic iron deficiency anemia, the cellular indices show microcytic and hypochromic erythropoiesis—that is, both the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) have values below the normal range for the laboratory performing the test.

- Peripheral smear. Examination of the erythrocytes shows microcytic and hypochromic red blood cells in chronic iron deficiency anemia; the microcytosis is apparent in the smear long before the MCV is decreased after an event producing iron deficiency.

- Serum iron, total binding capacity, and serum ferritin. Low serum iron and ferritin levels with an elevated TIBC are diagnostic of iron deficiency; while low serum ferritin is virtually diagnostic of iron deficiency, normal serum ferritin can be seen in patients who are deficient in iron and have coexistent diseases (eg, hepatitis or anemia of chronic disorders); these test findings are useful in distinguishing iron deficiency anemia from other microcytic anemias.

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis and measurement of hemoglobin A2. Hemoglobin electrophoresis and measurement of hemoglobin A2 and fetal hemoglobin are useful in establishing either beta-thalassemia or hemoglobin C or D as the etiology of microcytic anemia.

- Reticulocyte hemoglobin content. Mateos Gonzales et al assessed the diagnostic efficiency of commonly used hematologic and biochemical markers, as well as the reticulocyte hemoglobin content (CHr) in the diagnosis of iron deficiency in children, with or without anemia.

- Stool testing. Testing stool for the presence of hemoglobin is useful in establishing gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding as the etiology of iron deficiency anemia.

- Incubated osmotic fragility. Microspherocytosis may produce a low-normal or slightly abnormal MCV; however, the MCHC usually is elevated rather than decreased, and the peripheral smear shows a lack of central pallor rather than hypochromia.

- Tissue lead concentrations. Measure tissue lead concentrations; chronic lead poisoning may produce a mild microcytosis; the anemia probably is related to the anemia of chronic disorders.

- Bone marrow aspiration. A bone marrow aspirate can be diagnostic of iron deficiency; the absence of stainable iron in a bone marrow aspirate that contains spicules and a simultaneous control specimen containing stainable iron permit the establishment of a diagnosis of iron deficiency without other laboratory tests.

Medical Management

Medical care starts with establishing the diagnosis and reason for iron deficiency.

- Iron therapy. Oral ferrous iron salts are the most economical and effective medication for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia; of the various iron salts available, ferrous sulfate is the most commonly used.

- Management of hemorrhage. Surgical treatment consists of stopping hemorrhage and correcting the underlying defect so that it does not recur; this may involve surgery for treatment of either neoplastic or nonneoplastic disease of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the genitourinary (GU) tract, the uterus, and the lungs.

- Diet. The addition of nonheme iron to national diets has been initiated in some areas of the world.

Pharmacologic Management

Medications for iron deficiency anemia include:

- Iron products. These agents are used to provide adequate iron for hemoglobin synthesis and to replenish body stores of iron.

- Parenteral iron. Reserve parenteral iron for patients who are either unable to absorb oral iron or who have increasing anemia despite adequate doses of oral iron; it is expensive and has greater morbidity than oral preparations of iron.

Nursing Management

Nursing care for a child with iron deficiency anemia includes the following:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment of the child includes:

- Dietary history. A dietary history is important; vegetarians are more likely to develop iron deficiency unless their diet is supplemented with iron; national programs of dietary iron supplementation are initiated in many portions of the world where meat is sparse in the diet and iron deficiency anemia is prevalent.

- History of hemorrhage. Bleeding is the most common cause of iron deficiency, either from parasitic infection (hookworm) or other causes of blood loss; with bleeding from most orifices (hematuria, hematemesis, hemoptysis), patients will present before they develop chronic iron deficiency anemia; however, gastrointestinal bleeding may go unrecognized.

- Physical exam. Anemia produces nonspecific pallor of the mucous membranes; a number of abnormalities of epithelial tissues are described in association with iron deficiency anemia; these include esophageal webbing, koilonychia, glossitis, angular stomatitis, and gastric atrophy.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Fatigue related to decreased hemoglobin and diminished oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

- Deficient knowledge related to the complexity of treatment, lack of resources, or unfamiliarity with the disease condition.

- Risk for infection

- Risk for bleeding

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The major nursing care planning goals for patients with iron deficiency anemia are:

- Client/caregivers will verbalize the use of energy conservation principles.

Client/caregivers will verbalize reduction of fatigue, as evidenced by reports of increased energy and ability to perform desired activities.

- Client/caregivers will verbalize understanding of own disease and treatment plan.

- Client will have a reduced risk of infection as evidenced by an absence of fever, normal white blood cell count, and implementation of preventive measures such as proper hand washing.

- Client will have vital signs within the normal limit.

- Client will have a reduced risk for bleeding, as evidenced by normal or adequate platelet levels and absence of bruises and petechiae.

Nursing Interventions

The nursing interventions for a child with iron deficiency anemia are:

Administer prescribed medications, as ordered:

- Administer IM or IV iron when oral iron is poorly absorbed.

- Perform sensitivity testing of IM iron injection to avoid risk of anaphylaxis.

- Advise patient to take iron supplements an hour before meals for maximum absorption; if gastric distress occurs, suggest taking the supplement with meals — resume to between-meals schedule if symptoms subside.

- Inform patient that iron salts change stool to dark green or black.

- Advise patient to take liquid forms of iron via a straw and rinse mouth with water.

Reduce fatigue

- Assist the client/caregivers in developing a schedule for daily activity and rest.

- Stress the importance of frequent rest periods.

- Monitor hemoglobin, hematocrit, RBC count, and reticulocyte counts.

- Educate energy-conservation techniques.

- Encourage patient to continue iron therapy for a total therapy time (6 months to a year), even when fatigue is no longer present.

Educate the client and caregivers about iron deficiency anemia:

- Explain the importance of the diagnostic procedures (such as complete blood count), bone marrow aspiration and a possible referral to a hematologist.

- Explain the importance of iron replacement/supplementation.

- Educate the client and the family regarding foods rich in iron (organ and other meats, leafy green vegetables, molasses, beans).

Prevent infection

- Assess for local or systemic signs of infection, such as fever, chills, swelling, pain, and body malaise.

- Monitor WBC count; anticipate the need for antibiotic, antiviral, and antifungal therapy.

- vInstruct the client to avoid contact with people with existing infections.

- Stress the importance of daily hygiene, mouth care, and perineal care.

Prevent bleeding

- Monitor platelet count; instruct the client/caregivers about bleeding precautions.

- Anticipate the need for a platelet transfusion once the platelet count drops to a very low value.

- Assess the skin for bruises and petechiae.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Client/caregivers will verbalize the use of energy conservation principles.

- Client/caregivers will verbalize reduction of fatigue, as evidenced by reports of increased energy and ability to perform desired activities.

- Client/caregivers will verbalize understanding of own disease and treatment plan.

- Client will have a reduced risk of infection as evidenced by an absence of fever, normal white blood cell count, and implementation of preventive measures such as proper hand washing.

- Client will have vital signs within the normal limit.

- Client will have a reduced risk for bleeding, as evidenced by normal or adequate platelet levels and absence of bruises and petechiae.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation for a child with iron deficiency anemia include:

- Baseline and subsequent assessment findings to include signs and symptoms.

- Individual cultural or religious restrictions and personal preferences.

- Plan of care and persons involved.

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s responses to teachings, interventions, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

- Long-term needs, and who is responsible for actions to be taken.

Marianne leads a double life, working as a staff nurse during the day and moonlighting as a writer for Nurseslabs at night. As an outpatient department nurse, she has honed her skills in delivering health education to her patients, making her a valuable resource and study guide writer for aspiring student nurses.